Frequently Asked Questions

- What is "bandwidth"?

- Where does bandwidth for schools come from and is there enough to go around?

- How does it get to a school building?

- Why are wired connections used to connect schools?

- How much last-mile bandwidth does the school building need?

- How do you get the internet in the school building to the students who want to use it?

- How do these pieces all fit together?

- Why does it seem like it's been particularly hard for New York City to get it right?

- So what is the problem in any one school building?

What is "bandwidth"?

Bandwidth is a measure of internet speed -- the amount of information or data (specifically bits -- the 1s and 0s) that can come to a computer from the internet (download speed) and go from a computer back to the internet (upload speed). "Bits" are the most fundamental, most atomic, unit of all digital communication.

"Mbps" stands for megabits per second and is a common unit used to measure the speed of internet connections. 1 Mbps is equal to 1,000,000 bits per second that can travel through a network. Slower network connections may be measured in Kbps (Kbps) - 1,000 bits per second. Very high speed connections will be measured in gigabits per second - 1 billion bits per second.

Conversions and examples:

- 1 Gbps = 1000 Mbps = 1,000,000 Kbps = 1,000,000,000 bps.

- Dial-up modems used to connect to the internet in the 1990s were usually 14.4kbps or 28.8kbps

- Early first generation "high speed" DSL and cable modem services were in the range of 500kbps to 1Mbps (1000kbps).

- A standard speed offered by Verizon's home FIOS internet service is 100 Mbps, approximately 100x faster than the first generation "high speed" internet services of 20 years ago.

- Some companies (e.g., Spectrum) now offer 1 Gbps home service, 1000x an early era high speed connection.

Bits should not be confused with bytes. A byte is eight bits. With eight bits - eight 1s and 0s - there are enough different permutations of 1s and 0s possible (specifically 256 combinations) that this amount of bits when used together becomes quite useful to programmers. So it is with bytes, not bits, that we measure things like files that get transferred on a network.

The following picture is of a school in the Bronx. The size of the file that contains this picture is 52,000 bytes. Given there are 8 bits in every byte that means there are 416,000 bits in this file. If an internet connection can transfer data at 1Mbps (1,000,000 bits per second), it will take just under a half second for this image to be transferred from the server on which its hosted to your computer.

Where does bandwidth for schools come from and is there enough to go around?

New York City, given its prominent global stature, is generously supplied with bandwidth to the city. Internet bandwidth comes through the physical lines, owned by large global telecoms, that pass under the Hudson and East Rivers. These telecoms in turn sell internet access to homes and businesses. Some telecoms also choose to resell/wholesale bandwidth to smaller internet service providers who work directly with home and business end users.

The internet traffic for devices of the administrators, teachers, and students working and studying in the 1,300 buildings that comprise the NYC DOE physical plant is routed, like a funnel, through one gateway to one of these private internet service providers. The DOE recently completed a bid process for a new internet service provider to increase total gateway capacity from 24Gpbs to 240Gbps, a 10x increase. Lightower won the contract in late 2017 and is in the process of doing its upgrade.

How does bandwidth get to a school building?

The problem with internet access to schools really starts with getting enough bandwidth into the school building itself. There are two components to how internet traffic gets from from the DOE's internet gateway (provided now by Lightower) to a school:

- First, internet traffic travels from the DOE's internet connection (Lightower) into large capacity fiber optic wires, leased by the DOE. These lines create a "ring" across the city that connect seven Department of Education "nodes" located around the five boroughs. A node is a meeting point of network connections, much like the the joints that might connect different water pipes in a plumbing system. Here's a photo of this ring visualized on a monitoring screen in the Department of Education's Network Operating Center:

- Second, traffic travels to schools whichever of these seven nodes on the ring is geographically closest to their building. The traffic the closest node to the school building travels through a wired connection, called a circuit, provided by either Verizon or Lightower. This connection from the school building to the closet DOE "node" is sometimes referred to as the "last mile" (and the problem of getting enough bandwidth through that connection the "last mile problem"). The speed of this connection may range from 10 Mbps to 100 Mbps. The DOE is currently in the process upgrade all circuits in the city to each school building to 100Mbps for single school campuses, 150 Mbps for shared campuses.

Together - the city's ring and its 7 nodes, as well as the individual circuits used to nodes on the ring to school buildings, are sometimes collectively referred to as the DOE's "Wide Area Network" ("WAN"), especially to distinguish these two components from the both the public internet and well as schools internal networks (Local Area Networks - "LANS", which are discussed in questions further down).

Why are wired connections used to connect schools?

Given the concentration of buildings and obstructions in New York City coupled with bandwidth requirements, wireless technologies are not yet practical at the price appropriate for connecting schools to the DOE within the city, despite the recent evolution in high bandwidth wireless technologies. An exciting development worth watching too is mesh networking, which uses low power, short distance wireless connectivity that is less dependent on a central connection point. For the foreseeable future though last mile wired connections will be the norm.

How much last-mile bandwidth does the school building need?

If you have only enough water to run your sink but not your sink and your toilet, you don’t have enough water coming into the house. The same holds true for bandwidth to the internet - just as there needs to be enough water pressure for each toilet and shower, there needs to be enough internet - enough bandwidth - to serve everyone who wants to use it in a school building.

How much bandwidth is needed in a school? A common refrain is that all schools need "high speed internet" or "broadband". Until 2015 the FCC definition on "high speed" was 4Mbps when the FCC definition was upgraded to 25Mbps.

The FCC also provides some guidelines for how much bandwidth is required for various common internet uses, including

- "General Browsing and Email - 1 Mbps"

- "File Downloading - 10Mbps"

- "Streaming Standard Definition Video - 3-4 Mbps"

As context before 2007 the NYC DOE used an older technology to provide last mile connections (called "Frame Relay"). In 2007 the DOE started the process of upgrading its last mile connections with newer technology to bring schools to a total bandwidth of (at least) 10 Mbps. This target has since been revised to a target of 100 Mbps per school, 150 Mbps, and schools' last mile connections are in the process of being upgraded.

Back to the question of if there is enough bandwidth. Based on the FCC guidelines let's assume in a single school the following:

- 10 administrators are using the network for email and general browing (10 x 1Mbps = 10 Mbps)

- 30 students are downloading files for a science project (10 x 30 = 300 Mbps)

- 20 students in a lab are viewing a streaming video portion of an online literacy program (20 x 4 = 80 Mbps) The total required bandwidth for this very modest usage scenario is 390 Mbps, nearly 4x to the target for individual school bandwidth.

What are the implications of the aggregate bandwidth exceeding what's available? It’s not unlike if you have only one sink or shower in your house, or worse yet only one toilet. If everyone has to “go” at the same time, someone is going to have to wait. In the case of actual schools and networks, administrators will probably not notice much lag as they use email. However the lack of enough bandwidth does mean that students downloading files will spend more time waiting and hence less time on task. Some students' file downloads may time out causing them to have to restart downloads, wasting still more time. The students watching video lessons will experience buffering that both distracts from the presentation and makes the video take longer than planned. We've each probably experienced something similar when too many people try and use hot water at the same time in a house -- someone ends up with a cold shower.

How do you get the internet in the school building to the students who want to use it?

Assuming there is enough internet ((enough "bandwidth")) available through the network connection to the building ("the last mile") to support all concurrent internet users at a school concurrently, how does it get to the students who are spread out in different places in the building?

In technical language this problem is solved by distributing bandwidth either by wires in the building or through the air wirelessly using a technology called "WiFi".

Nowadays in New York City District schools, it's the various administrators' computers in the main office, along with a desktop computer in a classroom for teacher use, that are those connected by wires. The wires are cabling designed for networks that in the jargon are called "CAT 5" or "CAT 6" cables, and are run in the walls. These cables looks like telephone wire (itself technically called "CAT 3") but thicker with slightly bigger, wider jacks. Those of you who use the internet in an office setting 20 years may have had short 3' or 5' versions of these, often simply referred to as a "network cable" that they carried with them to use to connect to the office network.

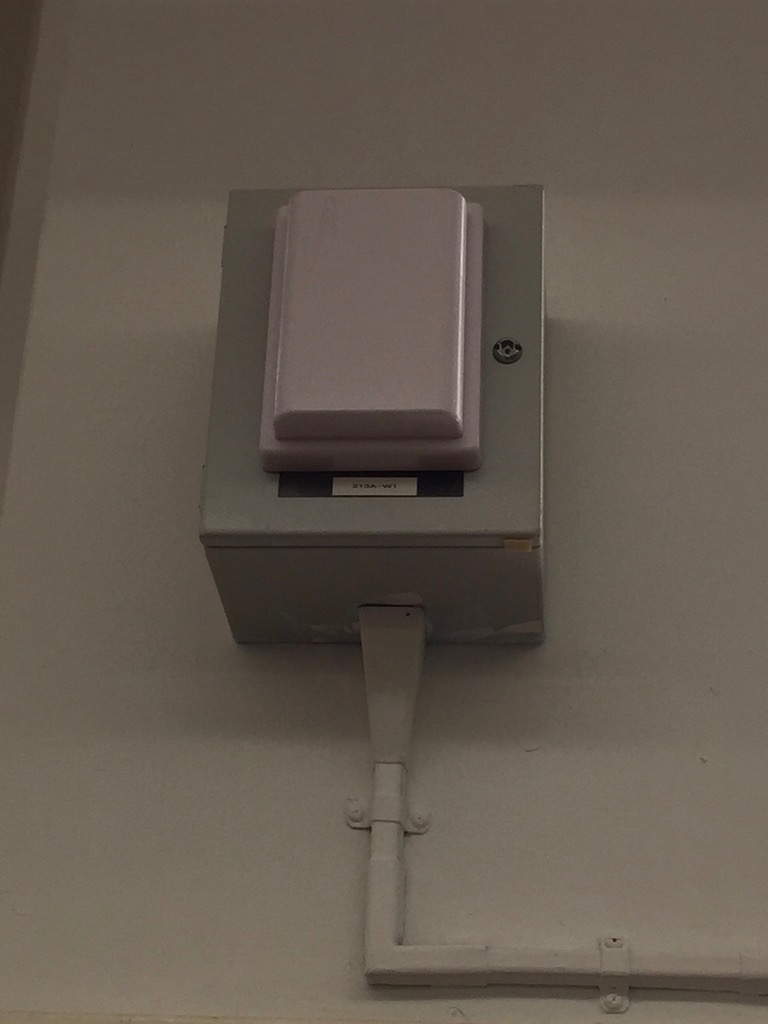

The majority of a schools' internet users, especially students, connect wirelessly using WiFi. Using Wifi, bandwidth comes to their device (e.g., a laptop) through a radio signal than emanates from a nearby "Wireless Access Point" (a "WAP"; example from a DOE school pictured to the right). The "WAP" is connected to the "last mile" using the same physical network for CAT 5 or CAT 6 cables that connected devices, like office desktops, that used wired connections.

The majority of a schools' internet users, especially students, connect wirelessly using WiFi. Using Wifi, bandwidth comes to their device (e.g., a laptop) through a radio signal than emanates from a nearby "Wireless Access Point" (a "WAP"; example from a DOE school pictured to the right). The "WAP" is connected to the "last mile" using the same physical network for CAT 5 or CAT 6 cables that connected devices, like office desktops, that used wired connections.

One of the early problems Wifi helped solve, especially in older schools that may not have had extensive wired networks, was to create more areas on the building where the internet could be used, so long as those devices could be reasonably close to a WAP that itself has to be connected to a wired connection.

Developments in WiFi technology have improved the range of WAPs as well as the the amount of connections a single WAP can handle. But just as technology has improved, so too have the amount of devices connecting and the amount of bandwidth each device uses increased. The amount of WAPs in a school, their location, and their physical power which manifests as the strength of the emitted radio signal all are important factors in the speed and reliability of the WiFi portion of a school network.

How do these pieces all fit together?

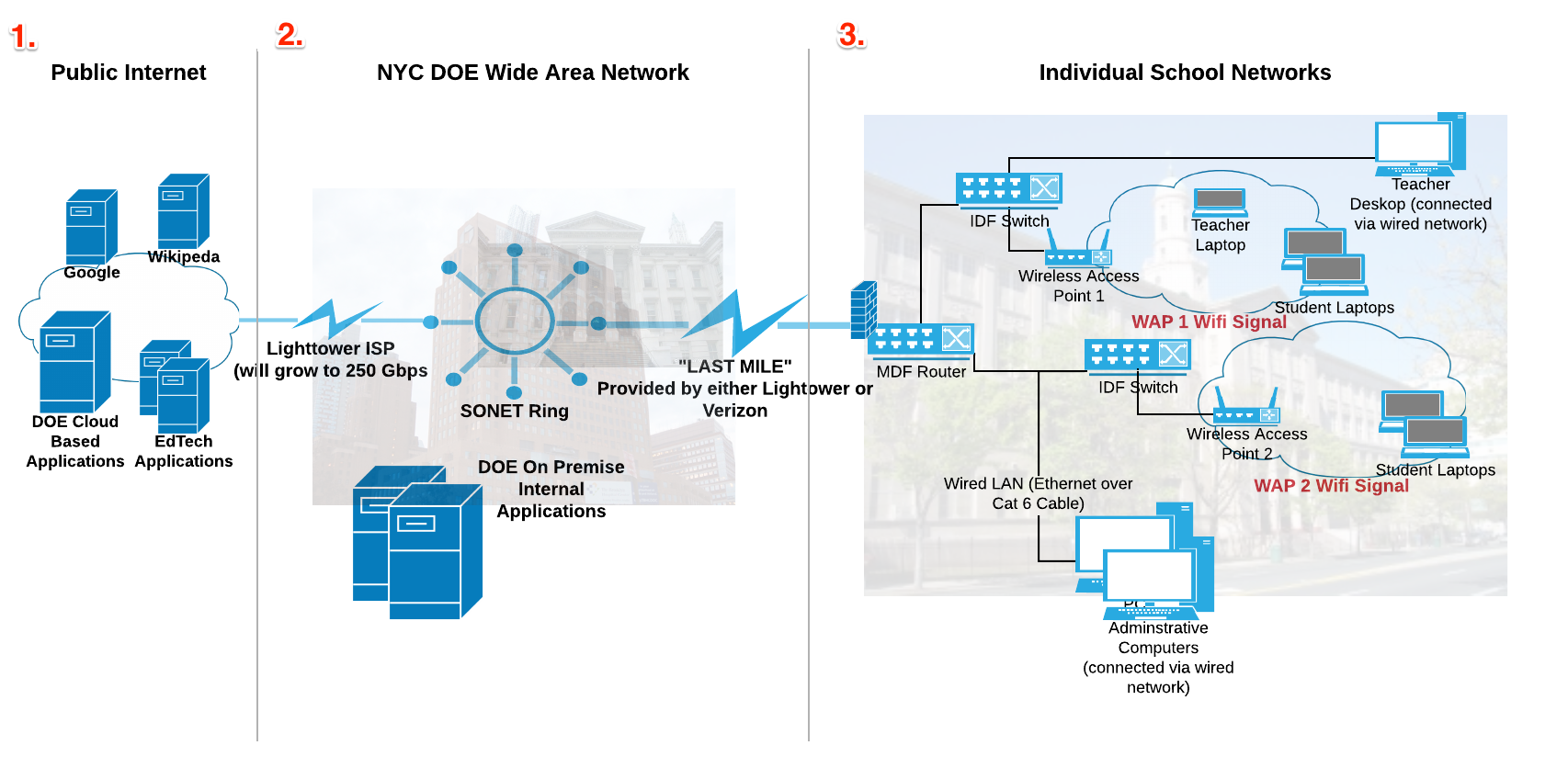

How does this all - the public internet and the DOE connection to it, the DOE ring and nodes that compose its WAN, the last mile, and schools' own network work in tandem?

See the following diagram:

The key components are:

- The public internet. The internet is the largest wide area network of them all. To the internet is connected the various resources a school might access including Google, Wikipedia, an online learning management system, various "backends" to applications on phones and laptops, and "cloud" services such as Dropbox

- The NYC DOE wide area network. This includes the ring that connects nodes around the city as well as last-mile connections. It also includes any applications and services that are hosted by the DOE themselves.

- A schools' local area network. This is all of the equipment, cabling, and wireless within the four walls of the school.

Why does it seem like it's been particularly hard for New York City to get it right?

[Note for Peter: I think I know which projects and budgets you are referring to here, but it would be helpful if you could spell each out so I can propertly reference and desribe them] In 2007 New York City began installing cables, connections and other things required to provide high speed internet to school buildings. The city spent a lot of money, (over $300 million) and by some accounts it did not put adequate controls and oversight in place to ensure that the system-wide upgrade was done properly or within budget. Surveys done by various people show there are serious limitations on the availability of high speed internet in schools, particularly in areas of underserved students.

In June 2017 New York City asked that companies bid on the right to upgrade the system and has $750 million allocated in a master plan to do so by 2020. Experts point out that there are serious questions about how the money will be spent and whether by the time the planned upgrades are done they will be adequate.

So what is the problem in any one school building?

This is the multi-facetted, complicated question. Some common problems include:

- Insufficient Bandwidth to the school itself. The "last-mile" "pipe" is too small to carry the aggregate bandwidth going to and from the various devices with in a school

- Too many users. While ideally the last-mile capacity should be able to handle growth in use, the network can become overwhelmed if many more devices are put on the network than the number for which it was planned. A common cause for this is when students are given the passcode needed to connect to the network and then share it resulting in a large number of personal devices being connected to the school network.

- Underpowered and overused WAPs. The WAP in a classroom is not powerful enough to handle all of the students at the same time.

- WAPs too far from end users. WAPs are not located near to where users need them.

These problems may also exist in combination, compounding each other.